Last Updated on August 21, 2023 by Allison Price

Learn the basics of horse conformation from an expert horse-judging judge so that you can’see’ horses like a pro and master judging terminology once and for all.

Your horse-loving friend might say to you, “That horse just doesn’t look right” or refer to a famous performance horse like “Wow!” He’s gorgeous! He is beautiful!” She can’t seem able to answer your question about why she prefers one horse over another, leaving you scratching your heads.

Although “look” is a significant factor in why a rider might choose a horse over another, it’s not the only thing that matters. There are many other factors involved in assessing a prospect. Good conformation is often closely related to good looks. This is based on principles of horse anatomy. An horse with a proper internal structure or anatomy will be more efficient and move more easily, making him able to perform better in sport and for longer periods of time.

This is where I will take the confusion out of conformation. I will show you what’s good and what’s not so good, as well as why. You’ll learn how to read common horse-judge jargon so that your next horse friend or you can “just like” it, you’ll be able to see the reason and use the language to explain why.

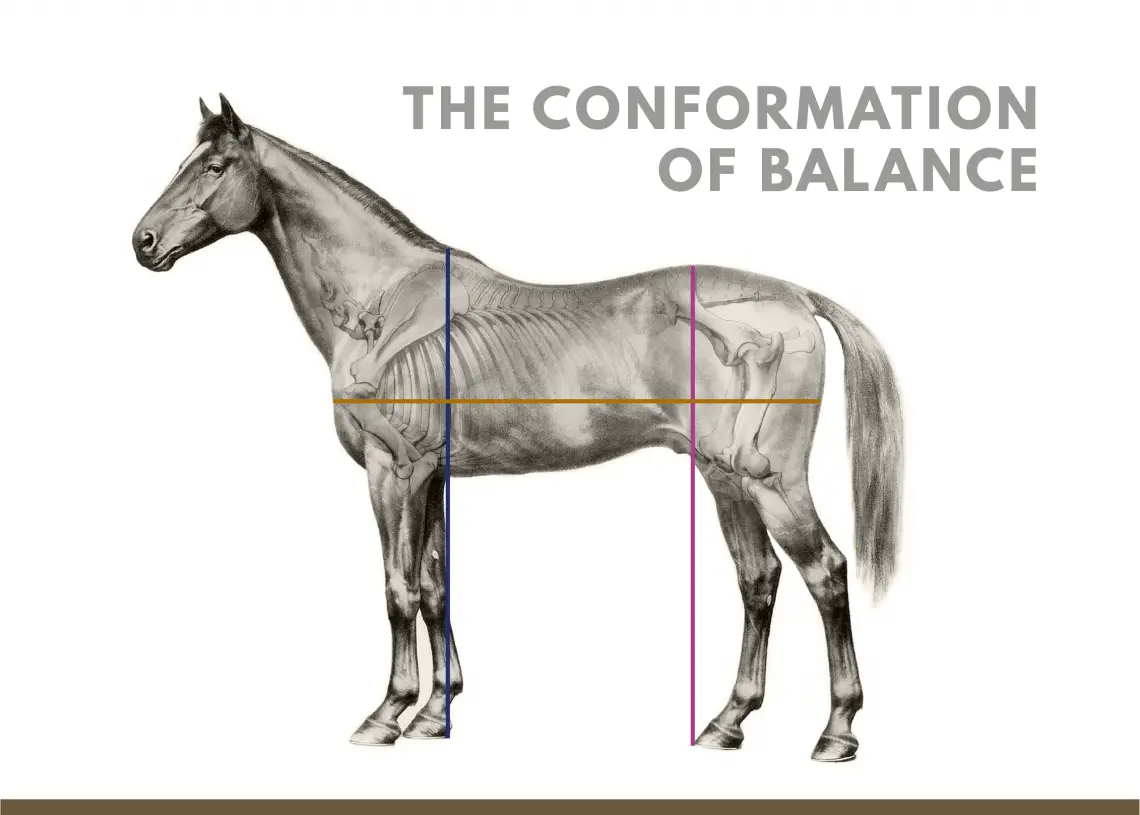

Balance

Balance is the foundation of good conformation. This is what good horsemen love. Horses with good balance have a pleasing profile that appeals to the eyes. Three areas of the horse’s body contribute to his balance, and allow him to appear cohesive.

Splitting a horse in thirds at the hip and shoulder will allow you to assess his front (by measuring the depth of the shoulder), middle (by measuring the length of his back, midsection and hip) and hind (by measuring the depth his hip). Good balance means that a horse will have equal length in each of these three sections. You can measure his shoulder length with a string, but you don’t need to measure his hips or topline.

His proportional balance is affected by the inequal length of any one or more of these parts. Inequality reduces the visual blending of all body parts and hinders athletic potential. A horse that has a shorter topline than his hips and shoulders will have weak shoulders. The extra length of his topline (or middle third) could lead to a horse developing a swayback or reducing hind-end function. Horses’ hind end is their motor. Inability to harness this power can affect his movement. Athleticism will also be affected by a horse’s shoulders being too short. A horse with too short shoulders will be heavy on his front end and carry his weight forward of his feet. This results in a sharper breakover of his knees which can cause more jarring movement.

Structure

Good structure is key to achieving a good overall balance. Good structure will make a horse more durable and athletic. These are just a few examples.

This stallion shows the best qualities of good conformation. He is balanced, well-built, and very attractive. He has a lack of muscle volume, and a less-than-ideal croup. These are his minor flaws. You can see that his tail is a bit straighter than his croup. The horse’s shorter conformation allows for quick and agile movements.

The shoulders

I have stressed the importance to have a horse with good shoulders and in proportion to other parts of his body. Good length is a positive thing, but horses won’t be able to move well if it isn’t straight up and down, rather than laid back and sloping. The ideal shoulder angle is 45 degrees in relation to ground. Any deviation from this is acceptable. A short, choppy stride will result if there is too much uprightness. A well-sloped shoulder allows for more forward reach in his front legs which allows him to cover the most distance with minimal effort.

The horse’s preferred slope doesn’t change depending on his size or the event. All horses should have well-laid shoulders, whether they are Western pleasure prospects, trail horses, or cutting horses. A taller horse is better for Western pleasure classes, while a shorter-framed horse can be used to cut or ride cow horses. The slope of a horse’s shoulders is not the reason, but his length, hips and limbs. The horse with a higher shoulder bone length can cover more ground per stride because he has longer shoulders. This type of conformation is illustrated in Horse 3, page 72. Because he has smaller shoulder bones, a shorter horse can move faster and more agilely. This type of conformation is illustrated in Horse 1. A horse will be athletic and well-balanced if he has good angulation in his shoulders. A horse with a bigger frame will have a wider chest, longer hips and a longer back in order to be balanced.

The pasterns

Complementary structures are often found beneath horses with long, sloping shoulders. A proper shoulder structure allows front legs to travel straight into the horse’s pasterns with proper support. He will track straight and be more comfortable when traveling. A horse’s ability to ride comfortably and be resilient under physical demands will depend on how soft his feet land. The horse’s pasterns are shock absorbers and should match the horse’s shoulders in slope. The length of the pasterns is the most important factor in proper angulation. Too long pasterns can be too relaxed and too close to the ground. This will put excessive pressure on the lower legs. Too short pasterns can be too straight and not absorb concussion well. This causes a choppy stride that leaves the horse vulnerable to injury and lameness.

This gelding’s hips and shoulders are too long for his height. He also has a low-tying neck, and sickle hocks.

The hips, hocks

Ideal horse posture is to have his hips slope in line with his shoulder angle. This allows him to reach under himself and take long rear-leg strides.

This gelding’s hips and shoulders are both adequate and complement each other. He has a lower-tying neck and better hocks than Horse 2. He is taller and has longer shoulder bones which allows him to cover more ground in each stride.

Athletic maneuvering and stride are both dependent on the hocks. Proper set is when the hocks are in the correct horizontal position relative to the point of the horse’s hips. Imagine a straight line running from the horse’s hip to his hock and down to his back. Proper flexion is possible when horses have enough angulation in their hocks. He can then reach his hind legs towards his belly and track straight behind his front legs. This ensures his power comes from his hind legs, and equal stress distribution throughout his leg. Inadequate angulation of his hips can cause pressure to build up in his legs, which makes him more vulnerable to injury. Horses with hocks too far back than the point of their hips can be post-legged. He will have a rough gait, and he won’t feel any impulsion from the hind end. This could lead to injury by concentrating stress on his stifles or pasterns.

The neck and topline

Strong toplines mean that a horse’s topline is straight from his point of withers to his hips. This strengthens his topline, allows him to engage his hips and keeps his front end light. His weight shifts forward if he is taller at his hips and lower than his withers. This can lead to a front-heavy, jarring stride.

The mare is a good height and has a decent length from her hips to her shoulders and hips, but her middle part is too long. She might be sickle-hocked, if she was standing normally.

A horse’s ideal back should be half the length of its underline. This will allow him to lift his hocks with greater power and ease. If the ratio is not equal or his back is too long, it will be more difficult for him gain collection. He’ll also have a hollow back which won’t allow his to engage his rear end, his power source. He will struggle to lift his hind legs under himself for effective stops and other maneuvers.

The same one-to-two ratio applies for a horse’s neck. Horses use their necks to reach forward and keep balanced, while they extend their stride or collect themselves. Athleticism is hindered by a neck that’s equal in length at the top and bottom. He will be able to maintain proper neck alignment and allow for free movement of the front legs by having a high neck-to shoulder tie-in.

Muscling

Athletic maneuvers can be made possible by adequate muscling. However, muscling is not more important than other areas of conformation. While proper nutrition and exercise can help build muscle and substance, proper balance and structure is not possible. Genetics can play a part in horses’ ability to or inability carry muscle. This affects the horse’s potential. A horse’s ability to muscling well is more important than bulk and volume. High-volume muscling, especially in the shoulders, that is often seen on halter horses is not necessary for most stock horse jobs (e.g. reining, cow horse trail and Western pleasure). High-volume muscles are essential for events like barrel racing and roping. There is a difference in the expression of muscles depending on how a horse uses them.

The gelding’s upright shoulders make him appear to be standing on his toes. His hips are not aligned with his shoulders. His structures are so different that his stride is shorter and more choppy.

Qualitative

Gender and breed characteristics can enhance the horse’s appearance and eye appeal. Gender characteristics are crucial when breeding animals. The feminine characteristics of mares are more delicate and feminine. Stallions look more masculine than both mares or geldings. Ideal for geldings is a kind and wholesome appearance. No matter the horse’s gender, there are certain desirable traits that all horses should possess. A perfect head should be short from the eye to the muzzle. It should also have a good expression in its face. A masculine, well-defined jaw is an ideal feature for stallion. There are some differences in the breed characteristics of stock-horse horses and lighter-breed horses. An Arabian, for example, has a slightly curved forehead and a profile that is more refined. His ears also have a slight inward curve. It is acceptable for gaited horses such as Tennessee Walking Horses to have slightly longer faces, from eye to mouth.

Horses that are pleasing to the eyes attract judges in the show pen and potential buyers at the time of sale. Try to find a horse with all the positive aspects of conformation at their highest level.